Through this past spring, The U.S.

Dollar had spent much of the preceding two-years weakening against the Euro,

despite the currency union’s sclerotic growth, inability to implement

structural reforms and the prospect of disintegration lurking in the shadows.

With demand for USD-denominated financial assets riding high and heightened

geopolitical risks nudging investors back towards the safety of U.S. shores,

one would have expected the USD to have powered past its advanced economy

peers. The odd performance of the USD

during this period may have been chalked up to America’s long-standing

inability to catalyze growth and even longer-standing inability to address

chronic fiscal imbalances. As the world’s default reserve currency, built-in

demand for dollars has enabled the country to get away with spending more than

it earns in a manner that would have sent investors fleeing from less revered

currencies. The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet also provided about

four-trillion other reasons why investors acted as if the USD was radioactive;

the fear being that with that much (potential…but not deployed) liquidity injected

into the economy, authorities may be unable stay ahead of a wave of

dollar-crushing inflation in years to come. What a difference six months makes. (to continue reading please click here)

The Stakeholder's Chartbook

Analysis of developments in financial markets, economics and public policy geared towards anyone with a stake in these issues......and, yes, we all have one.

Tuesday, November 4, 2014

Sunday, October 5, 2014

The Bond Rally Is Still Hanging On, But Now Is The Time To Consider Alternatives

Once again, news of the death of the secular bull market in

bonds has been greatly exaggerated, especially as the yield on the 10-Year Note

dipped below 2.4% on Wednesday. So continues the intellectual gymnastics around

the future of fixed-income markets, with key items of contention being, is the

multi-decade secular rally over?; how does the Fed go about unwinding a $4

trillion balance sheet?; what happens if monetary policy is behind the curve

should incipient inflation rear its ugly head?; and perhaps most vexingly,

should an advanced economy really be so dependent upon central bank largesse?

The last issue is all the more alarming given that six years of

zero-percent-interest-rate policy (ZIRP) and unprecedented financial market

intervention has only managed to deliver growth in the neighborhood of 2%.

Given the challenges of a low interest-rate landscape, many

a portfolio manager are grappling with novel tactics that enable them to meet

client obligations. In doing so, yet another phrase has entered into the

already convoluted lexicon of investing: unconstrained fixed-income funds;

unconstrained being a euphemism for "where on Earth do I find

satisfactorily yielding investments?" In an April note, when the 10-Year

Note yielded 2.8%, we turned bullish on bonds, given a lack of viable

alternatives… e.g. overheated equities…, an underwhelming recovery in

employment, and the expectation that even after the cessation of QE3, the Fed

would likely maintain ZIRP deep into 2015. So far we have been proven right. (To continue reading, click here)

Friday, September 5, 2014

The Emperor Has No Clothes: Emerging Market Investing Just Got Simpler

To say that the world is currently

rife with geopolitical turmoil and economic uncertainty would be an

understatement. Such periods usually mean a rough ride for risky assets as

investors shift their capital to safer havens until the storms subside. But these

are not normal times. Emerging market securities are often the first to

experience a pullback, yet the broad MSCI Emerging Markets Index has gained 8.5%

YTD after having spent 2013 in the red.

There are myriad explanations for

the rebound in emerging market (EM) indices this year. Some are due to bullish

fundamentals in specific countries. Yet one cannot ignore that in a

yield-starved environment, investors are clamoring for any security that

portends to offer an attractive return. Such demand-driven rallies….we call

them bubbles….have a tendency to disregard fundamentals, which obscures truly

attractive destinations for one’s capital and enables pretenders to take a seat

at the global financial markets table. Ironically, this overly-bullish,

top-down approach (which has more-than-once been in favor during the past

decade) is occurring at a time when heretofore major emerging economies are

running into stiff economic headwinds, backsliding on market-friendly reforms,

or in the case of Russia, putting geopolitical arrogance ahead of economic

development. To continue reading please click here.

Tuesday, August 12, 2014

The Recent Equities Slide: A Momentary Lapse of Irrationality?

In a January investment note, we

expressed caution towards U.S. equities, which at the time had been nearly five

years into a bull market. Not that we expected a strong correction, much less a

bear market, but it was unlikely that 2013’s 29.6% gain in the S&P 500

would be anywhere near repeated. Through the first eight months of the year, that

forecast has played out with the S&P up a more pedestrian 4.5%. We did not,

however, expect the index arriving at this point by initially sliding nearly 6%

before rallying 14% to a record high of 1,988. While the winter’s dip at first

appeared to be an outlier to the smooth upward trend (notice the nearly

parallel lines of the moving averages below), the recent 2.8% retreat has again

raised the eyebrows of more than a few cautious market participants.

At the time of January’s note, we

expressed the commonly held lament that while believing valuations had gotten

ahead of themselves, there were few alternatives to maintaining current stock

allocations given that cash returned zilch and the Fed was still gorging on

Treasuries, keeping yields in unappealingly low territory. With this in mind,

we suggested multiple options strategies that would lock in recent gains or

take advantage of certain names and sectors that had lagged the broader market

in 2013. These tactics (protective puts and purchasing calls) are still on the

table. To this, we would add another possibility: trimming one’s equities

exposure

(to

continue reading click here)

Monday, July 14, 2014

The Dollar: A Canary In The Coalmine?

For much of the current year, the

eyes of many in the investment community have been focused upon the continued

dubious rally in U.S. equities, which after stumbling out of the gate have

gained 13% since early February. At the

same time, the yield on the 10-Year Treasury has not broken much above 2.5%,

despite purportedly improving economic data, namely on the jobs front, as well

as the Fed’s announcement that the latest iteration of its bond-buying will be

wound down by autumn. Overshadowed by these developments has been a steady

weakening of the dollar. Over the past two years, the greenback has lost 11.4%

of its value against the Euro. And that’s against a currency that many thought

might not be around….at least in its present form….today. Granted there may

have been a sympathy bounce since the

nadir of the Eurozone debt crisis, but at what cost? Growth throughout the

currency bloc’s periphery continues to be strangled by austerity, and in the

name of doing whatever it takes to

exit the crisis, even the Germans have agreed to green-lighting Europe’s own

version of quantitative easing should it come to that, shadows of the Weimar

Republic be damned.

But it’s not just against the Euro.

The broader dollar index (DXY), a basket comprised of six major

currencies….albeit weighted towards the Euro…., has slipped 5.4% over the past

year. Two years ago, when the dollar was, relatively speaking, riding high, this

forum championed a strong dollar policy and the benefits it would bring to an

advanced economy such as the United States as well as to its financial markets.

Evidently no one was listening. Why would a forum geared mainly towards

mainstream investments venture into an esoteric asset class such as foreign

exchange? Three simple reasons: the dollar’s level and outlook impacts

virtually every other asset class, the same policy distortions that are

arguably driving risky assets higher are also sending the greenback lower, and

lastly…and even more sinister than the previous point….perhaps the day is

drawing nearer that the chronically weak U.S. fiscal position becomes too

egregious for markets to ignore, manifesting itself in an enfeebled currency

and all the economic headaches that accompany it.

Foreign exchange markets: caveat emptor

The foreign exchange market is

massive. How massive? The Bank of International Settlements puts the tally at

north of $5 trillion per day, making it the world’s largest financial market.

Theoretically…a loaded word in economics….the relative value of a nation’s

currency reflects the demand for the nation’s products and services (and thus

the local FX to pay providers), the overall growth prospects of the country,

its fiscal position, namely its ability to pay its public debt and lastly its monetary

policy, ideally administered by an independent central bank not coopted by

politics. In reality, the FX market is unlike other broadly traded assets in

the fact that the markets are blatantly distorted. Rather than having supply

and demand drive price and let the chips fall where they may, currencies are

manipulated by policies ranging printing money, which weakens it, buying up

excess local currency with foreign reserves to prop it up in shaky times, and

the setting of benchmark interest rates to levels which directly impact demand

for instruments denominated in a currency. One need not venture far past page

two in a financial newspaper to find contemporary examples of each of these

phenomena. In Vegas parlance, if you are a currency trader, you are playing

against a dealer with a loaded deck.

The dollar occupies a special

position in currency markets as it is the dominant unit used in settling

international commercial transactions as well as being the de-facto reserve

currency for the rest of the world. These result in built-in demand for dollars, which largely has given the country a

get-out-of-jail free card for decades when it comes to glaring fiscal

imbalances. Given its position as a reserve currency, along with

dollar-denominated Treasuries being the global standard for risk-free assets,

the greenback performs well in times of economic uncertainty, paradoxically

even when the source of said uncertainty is the United States (see the 2008

housing crisis). Normally such domestic tumult would send investors fleeing

from the transgressor’s currency. The economist Stephen Jen, formerly of Morgan

Stanley coined this concept the dollar

smile. When the world is seemingly on fire and flight to safety paramount,

the dollar rises. That is one side of the smile. If America’s economy is

performing well, relative to other global players, the higher growth

rates….accompanied by expectations of increasing interest rates….push the

dollar up as well. That’s the other side. In the middle, the dollar tends to

underperform when all the world is rosy and investors can pick off extra yield

in currencies that tend to have higher interest rates than the U.S. (think

emerging markets).

This is what makes the dollar’s

current slide so vexing. While not exactly in flames, prospect beyond U.S. shores

are hardly impressive. Japan has emptied its economic quiver in hopes of ending

two decades of malaise, with nearly all of its monetary and fiscal arrows being

Yen negative. The Eurozone at age 15 is going through an adolescent identity

crisis, unsure of what it wants to be when it grows up. And many emerging

markets have fallen back into old vices including state control (Russia),

politicians brow-beating central bankers (Turkey) and an inability to tame

inflation through sound policy (nearly anywhere in Latin America). By

comparison China looks lovely. But there growth is not what it once was, it has

a property bubble to deal with, and the state’s tentacles continue to firmly

grip the levers in key industries (e.g. banking), clouding commercial decisions.

Slow progress on the jobs front

Back in the U.S., after a shaky

start to 2014….far too conveniently blamed on lousy weather… economic data have

improved of late, namely on the jobs front. Skipping the population survey’s

headline unemployment rate (currently 6.1%), which is littered with so many

arbitrary omissions to render it meaningless, meatier data from the establishment

survey have indeed been strengthening. As seen below, the change in nonfarm

payrolls has been on a tear with the three-month moving average registering

well above 200 thousand in each of the past three months. This amount is

sufficient to absorb new entrants into the workforce as well as the legions

that continue to remain marginalized…those not

counted in the population survey….five years after the recession’s end.

Pandora’s box

The combination of rough seas

globally and steady….if not spectacular…improvement at home…should infer that

investing in U.S. assets is the only game in town. Looking at the S&P 500,

Treasuries and pockets of red-hot real estate prices, this appears to be the

case. But the dollar lags. Rather than benefiting from the aforementioned

dollar-smile, the trajectory of both the greenback and U.S. stocks can be

explained by another phenomenon: recent moves are likely the result of extraordinary

monetary policy. The Fed’s dominant role in absorbing less-risky bonds, which

has sent investors scrambling for yield in stocks and dodgier loans, has been

paid for with the dollar-negative expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet (upwards

of $4 trillion at last count) via the printing press.

The Terrible Trifecta

Exacerbating the problem is the

fact that the Fed’s indirect assault on the dollar could not have come at a more

inopportune time. For years economists have prophesized doom for the U.S.

currency (and the economy) should the country not get its fiscal house in

order. Yet the supposed benefit of quantitative easing….a return to robust

growth…has failed to materialize, and without a boost to government revenues at

the same time ever greater pressure is placed upon safety-net outlays, the

country’s fiscal position has only worsened. As seen below, the federal

government’s deficit is projected to remain above 6% this year. Granted the Fed

is stacking the deck in the Treasury department’s favor with artificially low

rates, but deficits at this level mean that interest obligations continue to

add to the federal debt, which remains over 100% of GDP.

Paying this down is complicated by

the fact that the U.S. is not a nation of savers, as evidenced by chronically

negative current accounts balances. The

dollar’s position as the world’s reserve currency has enabled the country to

get away with such imbalances, but at some point in the future, the willingness

of foreign investors to continue providing credit to such profligate spenders

may diminish. The risk is that far-off day may be drawing nearer.

Those who don’t study history are doomed to what?

A stated goal of Fed policy is to

drive up inflation expectations in order to cajole consumers to spend before

prices increase even more. The merits of such a tactic is questionable being

that excess consumption, along with its housing investment cousin, led to the

imbalances and credit overloads that drove the economy into deep recession. As

we have argued in the past, an economy dominated by personal consumption and

housing at the expense of business investment and exports is not equipped to

deliver consistent long-term growth.

It is true that headline inflation,

as measured by the Fed’s favored gauge has ticked up over recent months, but

much of this is attributable to one-off factors, that when stripped away,

results in a more subdued 1.5% year on year core inflation rate, well below the

Fed’s target of 2% or wink-and-nod limit of 2.5%.

The truth is that in an advanced

economy dominated by the service industry, a key driver of inflation is wage

growth. Unfortunately….and despite the improving nonfarm payrolls data….wages gains

have been miserable, averaging 2% annually since mid-2008 versus 3.3% in the

lead up to the crisis.

And What of a Strong Dollar?

Rather than seeking to ignite

inflation, which also debases one’s currency, authorities could have taken the

strong-dollar route. The U.S. is already a top investment destination both in

the form of portfolio investment (financial markets) and stickier foreign

direct investment, or FDI. A large

economy, strong legal framework, transparency and liquidity all contribute to

this. With the country in dire need of a catalyst to emerge from its 2% growth

funk, an injection of foreign capital would be a welcome development.

Expectations that the value of the dollar would rise relative to other

currencies would only add to the attraction of investing in America. Not only

does that translate into new factories, offices, and jobs, which then would spur consumption in a more

sustainable manner, but the jockeying for U.S. assets would provide fundamental

support to current corporate valuations, which by nearly all accounts, have

gotten a bit ahead of themselves. Another related dose of common sense would be

to reform the corporate tax code with the aim of reversing the current trend of

tax inversion through foreign acquisitions.

This exodus of U.S.-domiciled entities is precisely what the economy and

government coffers do not need at this juncture.

Weak-dollar apologists argue that a

diminished currency aids the country by making exports more competitive and

increases the value of foreign profits of American businesses, which account

for close to half the earnings pie. But trade is a small slice of the U.S.

economy and the country produces sophisticated capital goods that tend to be

inelastic to currency fluctuations. In other words, if your military needs a

U.S.-made fighter jet or your factory requires precision machinery, movement in

the level of the dollar will not likely deter your purchase. And who doesn’t

need a shiny new fighter jet? With regard to foreign profits, half of corporate

revenue is still derived domestically and the increased purchasing power that

accompanies a stronger dollar would stoke demand for foreign products, many of

which are produced by U.S. multinationals.

A weak dollar also has the…ahem…added

benefit of monetizing the country’s debt, meaning a cheaper currency lessens

the burden owed to foreign creditors. This is not the best way to win friends

in the international community. Then again, it’s not much worse than tapping

the private cell phones of the leaders of major allies.

Dear Washington: be careful what you wish for

One can argue deep into the night

whether or not the weakening dollar is an intended or unintended consequence of

current monetary policy. If it proves to be an ephemeral distortion caused by

recent extraordinary measures, perhaps the situation will right itself as the

Fed attempts to successfully exit various initiatives, which is by no means

guaranteed. More troubling is the prospect that the weaker dollar is a sign

that investors are growing more concerned about U.S. growth prospects, its

inability to control its fiscal position and the rapid encroachment of a

regulation-happy administration into the private sector. Should these concerns materialize,

U.S. investors and consumers will learn an unwelcome lesson on how a weak

currency can diminish a country’s investment returns and shackle its growth

prospects.

Monday, June 2, 2014

Commodities in 2014: A Place in the Portfolio?

At a conference in 2007, a speaker initiated

the proceedings by posing the question “what

are the most expensive words in the English language?” The answer to this was “it’s different this time.” The subject of the event was

commodities, namely whether or not the space had developed sufficiently to be

considered a viable asset class and a beneficial component of investors’

portfolios. During those heady pre-crisis days, the winds indeed appeared to be

at the back of investing in raw materials. So much so that experts filled

investment notes and the financial press with talk of a commodities super-cycle, driven by shifting

supply/demand dynamics and rising investor appetite, partly fueled by the

proliferation of new, accessible products.

During the crisis and its immediate

aftermath, the bullish case for commodities remained largely intact. This was

the period when emerging markets…a theme related to commodities demand….were

the engine that kept the global economy (barely) treading water. Aggressive

monetary policy also provided support to the commodities space as investors

ventured farther out along the risk spectrum in search of yield. A key attraction

to commodities during the roaring 2000s was that they had become a viable

source of returns, something that had eluded the asset class for decades. Since the initial post-crash period, which

was marked by the binary risk-on /

risk-off trade, with Treasuries encompassing the latter and nearly

everything else mindlessly lumped into the former, markets have shown greater

differentiation among asset class performance.

And during these past three years commodities have really taken it on

the chin.

As seen in the table above, even as

equities have sailed along at nearly a 16% annualized clip, total returns for

the broad S&P GSCI commodities index have dipped into the red, with the

agriculture and industrial metals buckets especially getting pummeled. Now, with U.S. equity indices hovering near

record highs, developed market bond yields at historic lows and trillions of

dollars in fiat money lurking in the shadows, an investor must ask if dialing

up commodities exposure at this time may at least in part address some of these

sources of consternation.

A history lesson

Long considered a niche investment,

commodities as an asset class have exhibited characteristics over the decades

that were attractive to investors. They lacked correlation to major asset

classes like equities and fixed income, meaning they could provide

diversification when included in portfolios. Not coincidently, they tended to

be positively correlated to the bane of many investments: inflation. The logic was that rising raw materials

prices squeezed corporate margins, thus diminishing the present value of a

firm’s future cash flow, which by definition meant a lower stock price.

Moderate inflation, driven by increased demand accompanying robust economic

growth could allow both input costs (e.g. commodities) and stock prices to rise

in lock step, but only up to a certain point before consumers get squeezed and

snap shut their wallets. Conversely, inflation caused by an adverse supply

shock of key raw materials…so-called cost-push inflation….seldom bodes well for

stocks. Similarly, inflation and bonds are akin to oil and water. Any whiff of upward

price pressure, regardless of the source, usually sends bond investors fleeing.

The downside to this inflation

hedge and lack of correlation has been the volatility inherent in commodities,

the difficulty in accessing them (historically available mainly through futures

contracts and the physical market), and perhaps most importantly, the absence

of any respectable yield. In fact, not only does a hunk of metal or bushel of

corn not pay a coupon or a dividend, but investors often incur holding costs

such as those for storage or rolling over expiring futures contracts, which

were priced lower than farther-dated replacements. Why were yields historically paltry? A simple

answer is supply and demand: For much of the 20th century, there was

plenty of easy-to-find oil, copper and arable land. As long as balances favored

supply, it was difficult for raw materials prices to go on a sustained tear.

Either producers would bring more product to market to meet increased demand or

incipient inflation would sour consumers’ appetites in what industry-types call

demand-destruction.

What fractured this status quo was, in a word,

China. Over the past three decades much of the world’s manufacturing capacity

was relocated this rising giant and to other low-cost countries. The industrial

base of these developing nations was less than efficient, meaning for every

unit of output, a greater amount of inputs was required vis-à-vis developed

markets. This was true for energy consumption, the utilization of metals and an

array of other raw materials. The lack of efficiency also applied to

nonexistent pollution standards, but no worries, none of that toxic air drifted

across the Pacific. Right.

At the same time these countries

were updating infrastructure and housing, increasing demand for construction

materials such as copper, steel and electricity (city dwellers are more energy

intensive than country folk). Not to be left out, demand for agricultural

commodities increased as large populations switched to protein-based diets,

which paradoxically, require a greater amount of crops like soybeans and corn

to fatten up cows and hogs for slaughter.

At the same time…..this was prior

to the shale revolution sent from above….cheap sources of raw materials began

to peter out. The crude, copper and aluminum were still there, but these

harder-to-access materials required additional expenses in R&D, exploration

and extraction, thus pushing up marginal costs. It was the confluence of this

increased demand inconveniently occurring as supplies were pressured that lent

credence to the super-cycle premise.

Sensing there was a buck to be made, the investment community funneled cash to

commodities firms to develop new resources; they also became active

participants in the physical and futures markets. Why a bank needs to own a

warehouse full of zinc is beyond me. But they did, resulting in increased

demand from financial…or speculative…players, who bought raw materials not to

produce anything, but simply to flip them and keep the profit.

The Shakeout

But this increased investor

attention led to an increased correlation between commodities and other risky

assets such as equities, undercutting one of the primary attractions of

commodities in the first place. The measures undertaken in the wake of the

financial crisis reinforced this development as yield-starved investors lumped

all riskier…thus higher yielding….asset classes into the same bucket. Rock-bottom

interest rates also played a role by making it cheaper to finance

highly-levered commodities futures. As evidenced in the chart below, beginning

in late 2008, the historical lack of correlation between equities and

commodities abruptly rose to a range consistently above 0.50.

Since the depths of the financial

crisis, it is safe to say that financial markets have returned but the economy

hasn’t. This dynamic is represented by commodities, as measured by the S&P

GSCI index, having traded sideways since mid-2011. Over the long-term,

supply/demand fundamentals (theoretically….a

loaded word) determine the prices for raw materials, and without robust growth

in major economies, the 2009-2011 rally proved impossible to sustain. The

divergence in fortunes between commodities and equities is also a reminder that

increased correlation refers only to direction and not magnitude.

Speaking of markets

Another knock against the increase

in speculative investors…as opposed to commercial users of physical commodities….is

that often their allocation decisions are driven by macroeconomic developments

rather than fundamentals. Yes, the participation of a certain amount of

financial players increases liquidity, thus market functionality, but when

taken too far, it distorts necessary signals from underlying supply/demand

dynamics. This was certainly the case in the two years immediately following

the crisis when the broad S&P GSCI returned a total of 25% and the energy,

industrial metals and agricultural buckets returned 20%, 70% and 32% respectively.

Since then, the broad index has returned -6%, with metals and crops getting especially

routed.

Certain segments of the commodities

universe are more tightly tied to economic growth. It should come as no

surprise then that two such sectors, energy and industrial metals, have suffered

over the past three years as global growth remains elusive. As seen below,

growth since 2010 has been on a downward trajectory for most global regions. Of

special concern is the lower rate of expansion in emerging markets, which had

been the shining star after the crisis.

With economies stuck in low gear, inflation

remains muted. While the Fed’s favored inflation gauge (below) ticked up to

1.6% year-on-year in April, the rolling three-month average is still a minuscule

1.2%, far below the 2.5% that they would happily accept. At the same time, the

Eurozone is flirting with deflation. It says a lot when Japan is more effective

in stoking upward price pressure than its advanced economy peers. Without any

inflationary pressure to hedge, a further rationale for commodities exposure

has been reduced.

Falling short of the promise

As it stands, commodities exposure

is not delivering what it has historically promised. Correlations with other

risky assets are elevated, meaning there are few benefits of portfolio diversification.

Even if the eventual curtailment of loose monetary policy chases away a large

amount of speculative investors…in turn lowering correlations…other merits of

owning commodities in the present environment also ring hollow. Inflation

remains muted and with global growth stuck in a rut, commercial demand for industrial

inputs will fail to match the rates registered earlier in the millennium. In

such a scenario, investors may as well chase asset classes like equities, which

despite dubious fundamentals, at least generate juicy returns.

The genie however is out of the

bottle and exposure to raw materials should remain on investors’ radar screens,

if not in their portfolios at present. Across the commodities universe, the new

sources brought online after the latest round of investment largely have higher

marginal costs than the fields, wells and mines of yesteryear. This provides a

price floor to many different resources. And if central banks get behind the curve of controlling upward

price pressure due to the mountains of money created to combat slow growth,

then the need for an inflationary hedge may indeed reappear, especially if

economic growth forecasts surprise to the upside…..but let’s not hold our

breath for that.

For those itching to for

commodities exposure today, one avenue is via the shares of commodities

producers. Historically these tend to be more correlated with the overall equities

market rather than physical market, but they are naturally levered (thanks to

firms’ balance sheets) and they’ve been outperforming the broader market of

late. Year to date, the energy sector of the S&P 500 has returned 7.5%

(including dividends), outpacing the 5% of the broader index. Materials, meanwhile

have returned a respectable 6.8% year-to-date. And there still may be more room

to the upside as both sectors lagged well behind the S&P 500 over the past

three years, with materials and energy returning 10.3% and 9.1% (annualized)

compared to the 15.2% registered by the broader S&P. And as evidenced by

certain segments of the physical market having tanked of late, investors may

finally be differentiating between slices with favorable and unfavorable

fundamentals. While not a complete

return to normalcy, this development means that those who do their homework can

be rewarded. The key is to identify resources

with long-term favorable demand dynamics and whose current prices are not too

far above the marginal costs of production, which in part may contribute to

limiting downside risk.

Friday, May 2, 2014

Connecting the Dots: The Financial Sector and the Economy

The banking sector never seems to

stray too far from the headlines of the financial press. And there is good

reason for that. Financial companies occupy a unique nook in advanced economies

as they serve as the transmission mechanism to allocate capital…in the form of

excess savings…to its most effective use, which are investments offering the most

attractive risk/return profile. Therefore an undeniable link exists between a healthy

financial sector and overall economic well-being. In addition to this broader

function, investors shower the sector with attention given that, even after the

financial crisis, it remains the second largest bucket of the S&P 500.

Investments are not like the

entertainment industry, where any publicity is good publicity. Sector stalwarts

continue to get raked over the coals for missteps in the run up to the

financial crisis. Recent headlines involving one key player’s (Bank of America)

error in reporting capital data are reminders of that. Also the current

earnings season, as usual, has been front-loaded with banking announcements,

which, while varying among components, collectively hints at challenges to

top-line growth, especially in key business segments like fixed income and

mortgage origination.

This week it is particularly

relevant to examine the banking sector as the Dow Jones hit a record high and

Q1 GDP data came in at a comatose 0.1% annualized gain. Divining the health of banks can shed light on

the….ahem….logic underlying the equities rally as well as whether or not we can

expect GDP growth, which finally showed signs of life in H2 2013, to rebound

after this past winter of discontent.

An inflated market raises all ships….justified or not

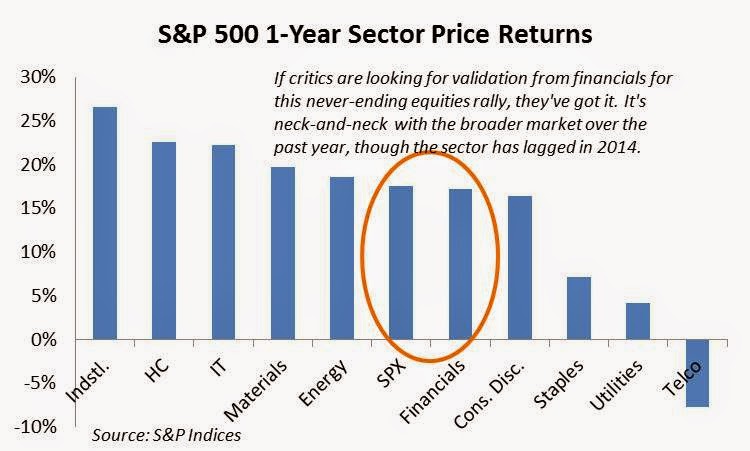

Investors love to say that equities

rallies need the validation of financial stocks. In the current instance, they’ve

got it….for the most part. Over the past year, excluding dividends, the

financial sector has gained a shade over 17%, only slightly below the 17.6%

registered by the S&P 500. For 2013,

financials actually outpaced the broader market, but have since come back to

Earth, being nearly flat year-to-date, while the S&P 500 is up over 1.5%.

Looking further back in time, one

can see the same story. Over one-year and three-year periods, on a total return

basis, financials have trailed the S&P 20.4% to 19.8% and 13.7% to 12.3%

respectively. Over a five-year timeframe, the delta is slightly larger with the

S&P’s annualized returns clocking in at 19% and financials, underperforming

at 16.9%. Over that length of time, two fewer percentage points makes a hefty

difference in total returns.

Of course the five-year returns encompass

the aftermath of the financial crisis, which includes the bounce-back year of

2010, making all the numbers appear a bit jazzier than they would otherwise. Since

then, the fact that financials have not joined more cyclical sectors like

industrials, consumer discretionary and IT in the upper echelon of returns can

be attributed to the regulatory constraints placed on the industry in the form

of higher capital cushions, the evisceration of their trading business and the

disappearance of the securitization cash cow.

Recent earnings reports from

leading banks tell this story. JP Morgan (JPM) saw its net income decrease and

Bank of America (BAC) recorded a net loss, in part due to litigation expenses

stemming from the housing crisis. The environment remains challenging for large

banks as every corporate treasurer and homeowner with a lick of common sense

has already refinanced, locking in historic low interest rates far out into the

future. So what had been a source of strength

in the early stages of the quantitative

easing era has become a shortcoming for both fixed-income divisions and

mortgage origination. Even Wells Fargo (WFC), which reported an increase in net

income of 14%, did so on the back of cost-cutting and not needing as many

reserves to cover loans previously considered suspect. Neither of those developments

can be relied upon for future growth.

Instead, what will be needed in coming

quarters is robust top-line growth and that can only come with an improving

economic outlook that entices bankers to lend out their considerable funds at a

substantially greater pace. Before jumping into that, we must ask the question whether

or not banking shares are attractively priced.

Discounted….perhaps for good reason

As seen below, based on estimated

full-year 2014 earnings, the nation’s five largest banks all have P/E ratios at

12.1 or under. These are at a discount to the 13.7 of the broader financial

sector (below) and dramatically lower than the 15.6 P/E ratio of the S&P

500. Banks are cheap on a Price to Book Value basis as well. But cheap does not

necessarily mean attractive. While the

sector as a whole has been aggressive in cleaning up the bad-debt mess from the

financial crisis…as opposed to European banks…one can see that some firms still

have lingering hangovers. Restrictions on dividends by authorities have

hampered growth of that previously alluring component of financial shares.

Prior to the financial crisis, when

financials were metaphorically printing money, unlike the Fed, which literally

printed it during multiple iterations of QE, investors were attracted to

banking shares, not just for their securitization-fueled growth model, but also

because it was the leading generator of dividends. And as we all know, the more

quickly a Board can return capital to shareholders, the lower the chance that

it goes off and funds some poorly thought-out acquisition (Countrywide comes to

mind). Even today, as seen above, the sector still contributes the second

greatest amount of dividends within the S&P 500. And this is with a

collective dividend yield of 1.8%, firmly in the lower rung of sectors (telco

is 5% and utilities are 3.8%). Imagine what financials could return if

regulators took their foot off of bankers’ throats?

Spring is here. Are the green shoots?

One cannot lay blame for the sector’s

woes entirely on its governmental overseers. After all, banks did take some

egregious liberties in their lending practices in the mid-2000s, which has

merited greater oversight. The other constraint hampering the sector is the

economy itself. Corporate borrowers don’t like uncertainty and will not

increase their fixed costs if future business prospects seem foggy at best. Even

if the economy gets a mulligan in Q1 due to a wretched winter, GDP growth has

still averaged a depressing 2% over the past 13 quarters. Similarly bankers

hesitate to lend in such environments for fear of getting stuck with a bunch of

dud loans. Ironically the same authorities that are encouraging banks to be

less parsimonious with their reserves are the same ones threatening to sue them

back to the Stone Age if their lending is deemed inappropriate or predatory…whatever

those mean.

With the exception of personal

consumption chiming in at 3% in Q1….evidently from brisk hot chocolate sales….the

remainder of the data was abysmal. Headline growth was 0.1%, which is one tick

from no growth. Nonresidential business investment dipped into negative

territory and housing fell off a cliff at -5.7%, following Q4 2013’s wretched

-7.9%. Yes some of that can be attributed to the cold, but higher mortgage

rates (albeit still low by historical standards), did not help matters.

We have previously argued the need

for the U.S. economy to rebalance

away from a reliance on consumption, which accounts for two-thirds of GDP.

Another favorite mantra is that residential construction should be a consequence

of a robust economy, not the source of it, as was the case prior to the crisis.

Resolution to those issues are years away however. In the here-and-now, the

economy needs robust consumption and a rebound in housing, which sends positive

reverberations through a range of other sectors. The problem is that, with a

weak jobs market, household formation has slowed to a crawl and in several regions

subdued wage gains impede the ability of

potential buyers to move upmarket from starter homes.

There are signs of optimism. As

seen in the confusingly squiggly lines below, lending standards for commercial

& industrial (C&I), auto, and general consumer loans have gradually

loosened over the past two years. Demand has also picked up for these loans to

meet this newfound supply. The sole exception has been mortgage demand, which

has taken a nosedive as rates have risen and cash investors have satiated

themselves after gorging on the market for years.

This thawing of the lending market

can be seen in the return to growth of outstanding loans. While C&I loan

expansion has been impressive over the past few quarters, growth in consumer

and real estate loans remains well below pre-crisis levels. As noted above,

these two areas have been major contributors to GDP growth over the past few

decades and additional credit flowing into them will be necessary in order to

increase the trajectory of what has been a frustratingly tepid recovery. On a

brighter note, the growth in C&I loans likely represents credit flowing to

small businesses…ones too small to tap the hyperactive bond market….which is

important given the role smaller firms play in creating jobs in the United

States.

A rightful place in the portfolio? Better than tulips.

So it’s all connected. Optimistic

banks, willing to lend, provide a needed catalyst in a highly-levered…euphemism

for debt-addicted…advanced

economy. A healthy economy further

instills the confidence of bankers and also rewards investors by juicing the

profits of financial firms. Somewhere in here there is a story about the wealth

effect and virtuous circles but it is 1:00 AM and my double espresso has

finally worn off, so we best not go down that path.

Should one own banking shares

today? At current valuations, why not? At the very least they help diversify

one’s portfolio, are naturally levered investments and many listings are still

sources of attractive dividends. Given the new regulatory hurdles of the

gargantuan Dodd-Frank law and the tepid pace of economic growth, especially in

debt-dependent sectors, there is probably not much room for upside. This is

especially true if one is of the belief that the rationale of this extended bull

market is tenuous at best.

Not to go totally macro but much depends upon the interest

rate environment and how the Fed shimmies out of its extraordinary monetary

policy. If one believes that the Fed will back off any threat to raise the Fed

Funds rate thus keeping short-term notes tethered to the sub 1% range, and that

excess liquidity (or a return respectable growth) will light the inflation

flame causing a sell-off in longer-dated treasuries, the ensuing bear-steepening of the yield curve will

be manna from heaven for banking net-interest margins. Conversely, if the Fed indeed

raises rates while growth prospects remain muted, the consequent bear flattening would squeeze margins

while at the same time discourage lending in the slow growth environment. Two divergent

scenarios; a question investors and committees must hypothesize over in coming

weeks.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)