Nothing like a few

sessions in the red after a nearly unbroken upward march in equity prices to

get investors…..belatedly….questioning the fundamentals underpinning the

S&P 500 at its record high. Since reaching 1,669 on May 21st,

the S&P has retreated in seven of the last 12 trading sessions and is

presently 1.5% off its peak. Before hitting the panic button….something

investors have evidently forgotten about…keep in mind the index finished last

week with two strong sessions…despite a luke-warm jobs report…and is still up

15.2% in 2013. Given last week’s rebound, investors do not seem overly worried

about equities venturing into such thin air. Any combination of three concepts

seems to be buoying sentiment towards the market. First, and the rosiest

scenario, is that investment analysts, being forward-looking and relatively

sharp, expect the economy to expand over the remainder of the year, which will

create a steady tailwind for (much-delayed) sales and earnings growth. A second

theory, especially popular during the early part of the year, is that markets

are benefiting from the return of retail investors who had continued to be in a

state of post-crisis shell shock. Under this scenario, pent-up demand for

shares as they climb higher would be enough to expand P/E ratios, thus creating

something of a virtuous cycle as more and more investors fear missing the boat.

Lastly, and most cynically, is the idea that equities are being driven by the

Fed’s policy of forcing investors further out along the risk spectrum in search

of respectably yielding assets. Under this distortion

scenario, equity gains are the function of macro-policy, virtually

disconnected from underlying company performance or economic developments. But

fundamentals do matter. And the recent stream of economic data causes the

neurotically risk-averse investor (the best kind) to lay awake at night

questioning current valuations.

Fearlessly Into the Stratosphere

Since November, the S&P 500 has

been on a tear. In classic bull-market style, lousy news is ignored and

anything marginally positive is reason to increase the bid. In a nod to

technical analysts, since the 50-day moving average crossed north of the

200-day moving average (this event alone being considered a bullish

development), the former line has provided a floor to any pullback in prices.

If you feel comfortable enough to

wager your kid’s college tuition fund on such concepts, then more power to you.

For those who prefer more

fundamentally-based rationale, there is some of that too. Based on earnings

estimates for the next four quarters compiled by S&P Indices, the S&P 500’s

forward P/E ratio is 14.6, still attractively priced by historical standards. One

must keep in mind that the much-ballyhooed P/E ratio has two components, the

price (numerator) and earnings (denominator). It is a positive sign that even

as investors have bid equities to record highs, the consequent expansion of the

P/E ratio has still left it at a relatively attractive…and plausible…level,

unlike during the dot.com bubble. But what is that price buying? The answer to

that is in the denominator, and it is less than encouraging. Again using

S&P Indices data, earnings estimates for the current quarter have been

revised down 4.7% since the beginning of the year. Third-quarter estimates have

been curtailed 2.6% and for the entire year, EPS has been trimmed by 2.4%.

Do You Still Love Me?

Much talk during this year’s first

quarter was that of the great rotation

from bonds into equities, which had been unloved since the nadir of the

financial crisis. These pages too delved into the subject, and like everyone

else, we clearly jumped the gun. According to data from the Investment Company

Institute, January’s surge into equities proved to be an outlier. Since then

flows into global equity funds have turned into a trickle. For U.S.-focused

funds, the situation is worse, with three of the past four months seeing net outflows.

This torpedoes the theory that

pent-up demand from previously sidelined retail investors will provide support

for a continued run-up in equity prices. This absence of inflows is also

reflected in muted trading volume during the rally. Below-average volume infers

that investors currently in the market are happy to let some players (likely pulseless

algorithms) jack up their portfolio values, but are not willing to allocate any

still-ample amount of idle cash towards additional share purchases.

Under the rosy scenario, if investors are correct then their bet on equities

will pay off in the form of GDP expansion, which will create fertile ground for

corporations to raise prices and undertake long-delayed hiring. In yet another

virtuous circle, this catalyzes demand from the country’s all-important

consumer segment. Recent data, however, has suggested the contrary is occurring.

Digging into the granular data imbedded in key manufacturing and employment

reports reveals that for the third year running the U.S. economy may in the

midst of yet another bout of subpar growth. (*note: and no, tepid data, which manage to beat low-balled consensus

estimates, are not reasons to pop the corks).

An Index Worth Paying Attention To

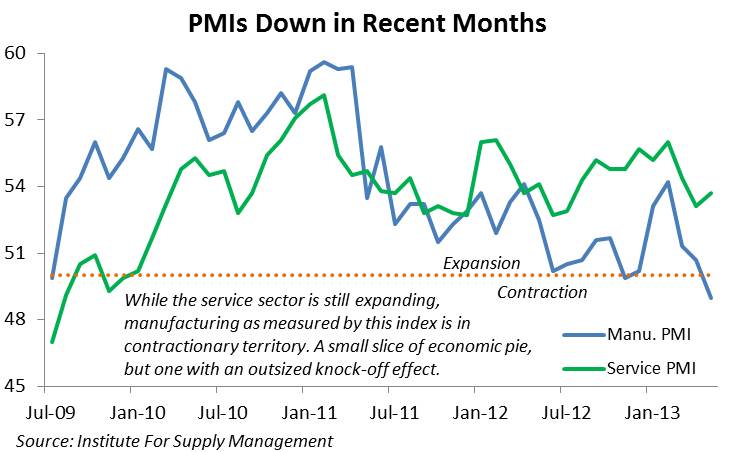

A favored economic barometer among

investors and strategists is the monthly PMI Manufacturing Survey conducted by

the Institute for Supply Management. As Alan Greenspan inferred, this index

gauges the outlook of corporate managers who have skin in the game by making

capital investment and hiring decisions. The chart below shows the trajectory

of both the more-established Manufacturing PMI and the newer Service PMI, which

tracks some 80% of the U.S. economy. While the Service PMI covers the larger

segment, the manufacturing index is considered a bellwether, given the multiplier

effect this sector has on the broader economy.

Since the beginning of the year,

both indices have been trending down, with the manufacturing PMI reaching into

contracting (sub-50) territory. That is not as dire as it seems. Over the past

several decades, manufacturing has continued to play a diminished role in the

U.S. economy, meaning that it often contracts even during the good times. The

ISM states that any reading on the manufacturer’s index over 42 infers that the

overall economy is still heading in the right direction. In that vein, May’s

reading of 49 is not the end of the word. But still neither index has enjoyed a

robust spring.

Perhaps more worrisome is the data

contained in the sub-indices. For manufacturers, a key barometer of future

demand is the relationship between new orders and existing inventories. If

inventories rise relative to orders, factories are likely to curtail production

until warehouses empty some of their shelves. For much of the past two years…and

especially in recent months…the difference between new orders and inventories

has been below average. With existing inventory sufficient to meet muted demand,

managers see little need to make capital investment or hire additional workers.

For much of the early part of the …ahem….recovery….the

nation’s manufacturers did more than their fair share to make up for the

traumatized, unemployed and deleveraging U.S. consumer. Much of the demand for

these factories’ products came from abroad, especially from emerging markets

keen to purchase high quality capital goods to build out their infrastructure

and update their manufacturing capabilities. This trend has grown long in the

tooth with both the production and exports sub-indices falling over the past

several months.

Related to this is recent data on

new orders for durable goods. A key component of this monthly report is

nondefense capital goods ex-aircraft, which serves as a proxy for business

spending. When companies are optimistic about future sales prospects, they are

more likely to invest in capital goods, which are often financed on credit.

Conversely, a lower level of orders infers that businesses have reservations

about coming quarters and may not want to make leveraged investment. This may

be what we are seeing now with the three-month average (to smooth out

volatility) for year-on-year changes in new orders dipping into negative

territory.

Lower investment by the nation’s

businesses can lead to lower productivity gains in the future and also hint

that firms may be equally unwilling to invest in additional workers. Back to

employment…and the PMI indices….jobs sub-indices for both the manufacturing and

service sectors have fallen over much of the year. As seen below, downward

trends in these indices (combined here) have largely reflected softness in job

creation as measured by the nonfarm payrolls report.

More Jobs: But the Wrong Kind

Friday’s jobs report showed a gain

in nonfarm payrolls of 175 thousand, roughly in-line with the 12-month average.

Good….but not good enough. Of the 8.4 million jobs lost by the height of the

recession, nearly three-quarters have been recovered. To absorb the remaining

two million….in addition to the nearly 150,000 that enter the workforce each

month, at the current rate (176k) it would take over six years. Not the news

anyone wants to hear.

Equally unsettling is which types

of jobs are being created. Since the beginning of the year, there have been 946

thousand new jobs created. But 38% percent of those have come from temporary

service companies ((111k), retail positions (93k) and food and beverage

establishments (160k). Being a barista or haberdasher is a noble way to make

ends meet during tough times, but these are not the high-paying jobs that will

lead to a renaissance in consumer spending. And as stated ad nauseum, at 70% of

the economy, personal consumption is a necessary component to any lasting

recovery. What is an example of jobs better suited for fueling overall economic

growth? Manufacturing is one. But from mid-2006 to mid-2009 the U.S. shed 2.49

million manufacturing positions. Since then, only 246 thousand have been

recovered. Would you like skim, soy or

2% milk in your latte, sir?

Retail Sales

With jobs data like this, one must

wonder whether the consumer can marshal the strength to be an incremental

contributor to economic growth in the near future. Any thought that that may be

the case is diminished when viewing recent retail sales data. Core retail

sales, which strips out auto sales, gasoline and building materials (and better

aligns with the personal consumption figure in GDP data), rose 3.3% YoY in

April; the worst reading since July 2010. The

respectable gains from the end of the crisis through mid-2011 are long

since passed, and much of those were likely the consequence of a base effect

from a truly horrific period in 2009 and early 2010.

Credit Cards to the Rescue

Paradoxically, there is one iota of

positive news on the consumer front. While nonrevolving credit for consumers who

actually won’t have a banker hang up on them has risen over the past two-plus

years, outstanding credit card debt has been the laggard. This has finally

begun to change with Q1’s YoY figure rising 1.6%. We’ll take the good news

where we can get it.

No comments:

Post a Comment